Markets fell on Tuesday, on fears, we are told, about weakness in mortgages and housing; this prompted Brad Setser to ask me whether I’m still as sanguine as I used to be on such matters. I couldn’t reply on Wednesday, since I went to Disneyland instead — I can highly recommend the Indiana Jones ride, if you find yourself there for whatever reason. While I was there, the market went back up again. As ever, my main conclusion from all this is that no one should ever draw any conclusions from one-day market moves.

All the same, I might as well get down here for the record what I think about mortgages and housing, because although I think that the bears have some enormous holes in their arguments, that doesn’t necessarily make me bullish.

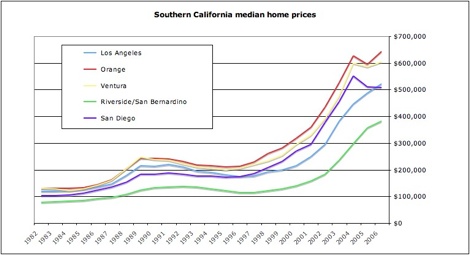

I basically start with the observation that the run-up in housing prices in recent years has been seen all over the world: from Spain to South Africa, from Ireland to Australia. Not everywhere has participated: there’s been a lot more price appreciation in Shanghai than there has been in Stuttgart. But there’s clearly some kind of global force — let’s call it “liquidity”, for lack of a better term — which has been driving asset prices in general, and housing prices in particular, upwards. What’s more, by the standards of many of these countries, the run-up in US home prices has been relatively modest.

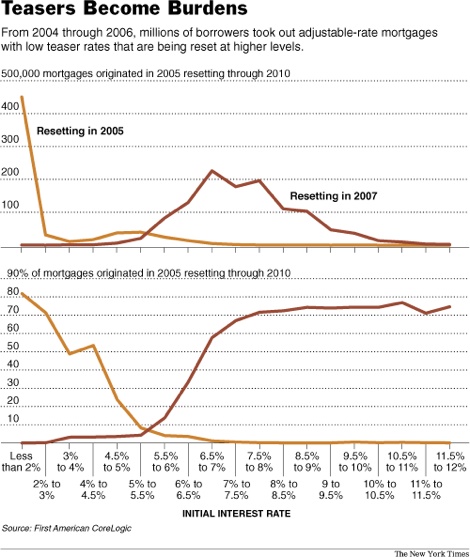

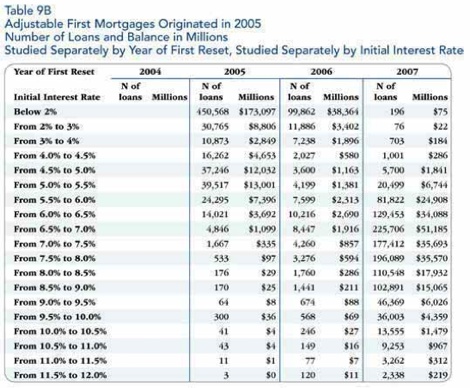

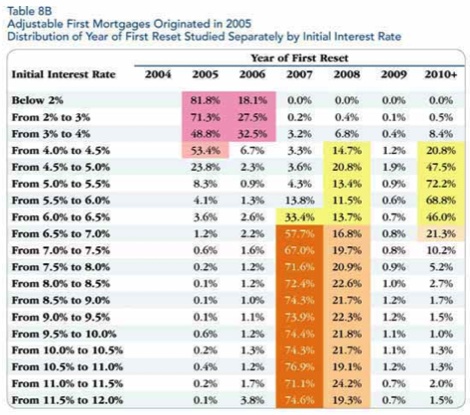

Let’s now take another look at the US. I don’t deny for a minute that the number of defaults on subprime mortgages, especially subprime mortgages of the 2006 vintage, is eye-poppingly high, and rising. What’s more, given the fact that originators have tightened up their underwriting standards substantially (and correctly), many mortgage holders are going to find it hard to refinance their adjustable-rate mortgages when they reset. This could drive default rates even higher, if the rates on those mortgages go up a lot. Home prices are still substantially above their 2004 levels, however, so the real problem is largely confined to mortgages originated in 2005 and 2006.

Now, it’s easy to paint a picture whereby defaults on recent-vintage mortgages cause a more generalized tightening in credit markets along with a plunge in housing prices as supply goes up and demand goes down. I do accept that, in theory, this could happen. But before I believe the prognostications of those who say it will happen, I want to see some indication that their model of supply and demand and housing prices actually reflects reality. Specifically, I want to see whether it explains the rise in housing prices over the past few years.

The big mistake that I think a lot of the housing bears are making is that they’re confusing correlation with causation. Yes, subprime credit has increased substantially in recent years. And yes, housing prices have gone up. But that doesn’t mean that the former caused the latter. Indeed, there are a good reasons to believe that the increase in subprime credit did not cause the run-up in housing prices. For one thing, housing prices started rising before the increase in subprime credit. For another, much of the increase in subprime credit was concentrated in depressed areas such as Michigan and Ohio, which accounted for 15% of all US foreclosures in January. And it’s precisely those areas which did not see a run-up in housing prices. Meanwhile, the market in New York City co-ops, for instance, has been booming (and shows few if any signs of slowing down) despite the fact that because those units are “non-conforming”, it has always been incredibly difficult to get a subprime mortgage on them. Finally, the rise in subprime credit in the US was not matched by a rise in subprime credit in places like South Africa and China, which saw much greater price increases — so whatever forces drove housing prices up globally are probably sufficient in themselves to explain the increase in housing prices in the US.

Now, one of those forces is doubtless an increase in the availability of credit generally, if not subprime credit in particular. If housing prices rose on a tide of global liquidity, then they can fall if and when that tide starts going out. For the time being, however, there are no signs that is happening. Yes, there are problems in one localized sector of the US mortgage market. But credit markets globally are still as tight as they’ve ever been. And the US subprime market is simply not big enough to affect global credit markets in any substantial way.

At the margin, then, problems in the US subprime sector will surely have some effect on the US housing market — although, obviously, the effects will be greatest where the concentration of subprime loans is at its highest. But I still think that the big drivers of the US housing market in the recent present will continue to be the big drivers of the US housing market in the near future — which does give me some cause for optimism.

One thing is certain, however: foreclosures will continue to rise, which will be personally devastating to hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of homeowners. These personal tragedies will resonate on Capitol Hill, and the federal government might step in to help those individuals out — which might, in turn, help mitigate the economic effects of the foreclosures. What’s more, all the talk of hundreds of billions of dollars being “lost” in foreclosures is a mite misleading: all that equity has already been lost by the time the foreclosure proceedings begin.

The big losers will be the holders of the equity tranches of MBSs and subprime-backed CDOs, as well as those subprime originators who find themselves holding a bunch of scratch-and-dent loans they thought they’d sold already. So it makes perfect sense that subprime mortgage originators are closing shop. But I’m not shedding too many tears for them: they made a lot of money in the boom years, and then they relaxed their underwriting standards far too much at the end of 2005 and the beginning of 2006. They deserve to bear the consequences.

As for the holders of MBS and CDO equity, we’re talking very, very sophisticated investors and financial institutions here, who are almost without exception both willing and able to bear those losses. I see no systemic risks there.

Looking forwards, the number of subprime loans originated will go down, which means that issuance into the subprime MBS market will fall. That’s fine. As the yields on those subprime MBSs rise and the underwriting standards on them tighten, there will be enough demand for them to meet supply. So I’m not particularly worried there, either.

The one big event risk, which hasn’t happened yet, is a mass downgrade of MBSs carrying BBB and BBB— ratings, to junk status. If that happens, there will be forced selling of those MBSs by institutional investors who are not allowed to own speculative-grade debt, and spreads are likely to gap out substantially. Given how the markets managed to cope with the Ford and GM downgrades, however, I think they could probably cope with this as well. (Remember that Ford and GM bonds are unsecured, and therefore have much more room to fall.) What’s more, at this point there’s no indication that such a mass downgrade is going to happen.

Overall, then, I’m sanguine about the US mortgage and housing markets. There will be large losses, which will generally be sustained by entities well able to afford them. On an individual level, there will be some tragic losses of much-loved homes. But on a systemic level, I think there is relatively little to worry about.

Oh, and one last thing: there’s an argument that US GDP growth has been reasonably healthy of late mainly because of the amounts of equity that consumers are taking out of their homes and spending in shops. If they stop doing that, goes the argument, then the US faces recession — and house prices never do well in a recession. Again, my response is simple: show me, plausibly, the degree to which home equity withdrawal boosted GDP growth in recent years. Then we’ll have a good idea how much it could affect GDP growth on the downside.