Brad Setser asks whether I’ve changed my mind about the mortgage market in the wake of today’s data and the market’s reaction to it. I haven’t really looked at either yet, and tomorrow I’m going to be spending the day at Disneyland. So do please use the comments section here to give me all the datapoints I need. Then I’ll answer his question on Thursday, probably.

Meta

Categories

- accounting

- Announcements

- architecture

- art

- auctions

- bailouts

- banking

- bankruptcy

- ben stein watch

- blogonomics

- bonds and loans

- charts

- china

- cities

- climate change

- commercial property

- commodities

- consumers

- consumption

- corporatespeak

- credit ratings

- crime

- Culture

- Davos 2008

- Davos 2009

- defenestrations

- demographics

- derivatives

- design

- development

- drugs

- Econoblog

- economics

- education

- emerging markets

- employment

- energy

- entitlements

- eschatology

- euro

- facial hair

- fashion

- Film

- Finance

- fiscal and monetary policy

- food

- foreign exchange

- fraud

- gambling

- geopolitics

- governance

- healthcare

- hedge funds

- holidays

- housing

- humor

- Humour

- iceland

- IMF

- immigration

- infrastructure

- insurance

- intellectual property

- investing

- journalism

- labor

- language

- law

- leadership

- leaks

- M&A

- Media

- milken 2008

- Not economics

- pay

- personal finance

- philanthropy

- pirates

- Politics

- Portfolio

- prediction markets

- private banking

- private equity

- privatization

- productivity

- publishing

- race

- rants

- regulation

- remainders

- research

- Restaurants

- Rhian in Antarctica

- risk

- satire

- science

- shareholder activism

- sovereign debt

- sports

- statistics

- stocks

- taxes

- technocrats

- technology

- trade

- travel

- Uncategorized

- water

- wealth

- world bank

Archives

- March 2023

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- December 2012

- August 2012

- June 2012

- March 2012

- April 2011

- August 2010

- June 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- September 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

- June 2005

- May 2005

- April 2005

- March 2005

- February 2005

- January 2005

- December 2004

- November 2004

- October 2004

- September 2004

- August 2004

- July 2004

- June 2004

- May 2004

- April 2004

- March 2004

- February 2004

- January 2004

- December 2003

- November 2003

- October 2003

- September 2003

- August 2003

- July 2003

- June 2003

- May 2003

- April 2003

- March 2003

- February 2003

- January 2003

- December 2002

- November 2002

- October 2002

- September 2002

- August 2002

- July 2002

- June 2002

- May 2002

- March 2002

- February 2002

- January 2002

- December 2001

- November 2001

- October 2001

- September 2001

- August 2001

- July 2001

- June 2001

- May 2001

- April 2001

- March 2001

- February 2001

- January 2001

- December 2000

- September 2000

- July 2000

- March 2000

- July 1999

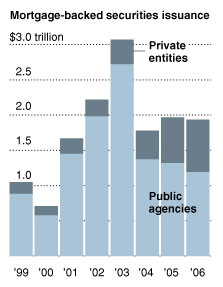

But here is Morgenson’s own graph, showing the practical effects of that churning mania: MBS issuance more than $1 trillion lower in 2006 than it was three years earlier. It’s very hard to look at this graph and see any evidence of a bubble: rather, it seems that private-sector MBS issuance has been rising only to make up for a large drop in issuance from Fannie and Freddie.

But here is Morgenson’s own graph, showing the practical effects of that churning mania: MBS issuance more than $1 trillion lower in 2006 than it was three years earlier. It’s very hard to look at this graph and see any evidence of a bubble: rather, it seems that private-sector MBS issuance has been rising only to make up for a large drop in issuance from Fannie and Freddie.