Robin Hanson asks for disagreement case studies. When I was at RGE, I developed a bullish, trust-the-market persona to act as a foil to Nouriel Roubini’s ultrabearish position. Brad Setser was kinda in between. The interesting thing to me, which I’m sure will come as no surprise to Hanson, is that I ended up believing my own posts so easily and so quickly. I wasn’t putting voice to positions I’d held for a long time — but by putting voice to those positions, I ended up holding them. Similarly, after writing 5,500 words in defense of vulture funds, I’m now more well-inclined towards them than I was.

But in any case, let me try to answer Robin’s questions with regard to the disagreement between me and Nouriel on whether weakness in the US housing market would drive the US economy into recession. Says Robin, by way of introduction:

You realize that both your opinion and theirs may result in part from defects, such as thinking errors or not knowing something that the other knows.

This is surely true. So to answer his questions:

Do you conclude just from the fact that they disagree that they must have more defects?

No.

Do you think they realize that they can have defects, such as thinking errors or knowing less?

Yes. Nouriel’s reasonably good at admitting when he was wrong. And if asked, I’m sure he’d say that there were some defects in his reasoning in those cases.

Should the fact that you disagree be a clue to them about their defects? Is it a clue about yours?

My disagreement probably should be a clue to Nouriel about his defects, but it’s easy to understand why it isn’t: for one thing the disagreement came out of a deliberate attempt to disagree with him, and for another thing I have no economic qualifications. On the other hand, after spending a lot of time around Nouriel it’s very easy to see my own arguments the way he sees them. So I think I’m relatively clued-in about the defects in my own arguments.

Do they adjust their estimates enough for the possibility of their defects? If not, why not?

Yes and no. If you look at Nouriel’s estimates, he generally gets to his predictions by doing a bunch of economics, coming to an insanely bearish world-is-coming-to-an-end conclusion, and then diluting the result enormously for no obvious reason until it comes to a point where it’s still an outlier but at least it’s not a massive outlier. If lots of other very smart people were all more bearish than his official estimates, I think his estimates would be much more bearish than they are — so yes, I think he’s adjusting his estimates in the light of extant disagreements. On the other hand, his adjustments are quantitative, not qualitative. He doesn’t assume that he might be wrong; he remains very sure that he’s right.

What clues suggest to you that they have more defects, or under-adjust for them?

Nouriel has achieved no small measure of fame and notoriety from being as bearish as he is — his bearish position has given him a large number of groupies who hang on his every word, and a widely-read blog which drives traffic to his for-profit website. So in that sense he has every incentive to under-adjust for defects in his arguments. Also, as an economist coming more from the academy than from the market, he’s more likely in my view to overweight arguments based on economic theory and less likely to look at the frequency with which predictions based on such theories have spectacularly failed to come true. He also cherry-picks datapoints, but we all do that.

What clues suggest to them that you have more defects, or under-adjust?

I have little if any equity in being right: I’m blogging to have fun, jumping into the debate with both feet. I know that my opinions aren’t particularly considered, even though I do believe them to be right. Also, I’m not an economist, so I’m quite unqualified to opine on matters economic — not that that ever stopped me.

Do you both have access to these clues, and if so do you interpret them differently?

Yes. But I think that Nouriel underestimates the degree to which frequently reiterating a bearish position serves to overstrengthen the arguments for it in his mind and decrease whatever objectivity he might have. I wouldn’t have believed it myself, if I hadn’t observed it in myself at first-hand: the way in which I became a bull simply by writing a bullish blog.

Do you each realize some clues might be hidden?

Probably not.

Does your inability to answer any of these questions suggest you have defects?

I’ve never claimed that I didn’t have defects.

Consider all these questions again for your meta-disagreement about who has more defects.

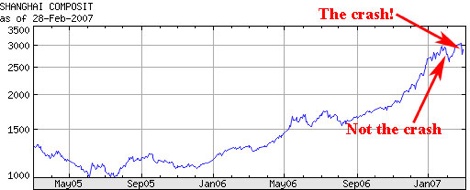

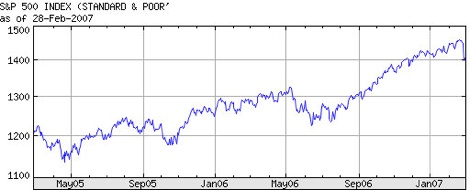

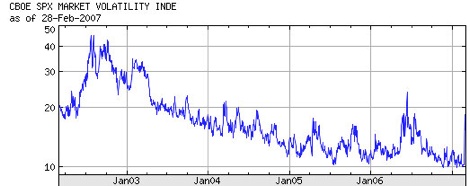

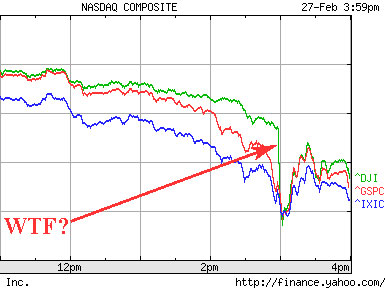

I’m really quite uninterested in who has more defects, mainly because which of us has more defects has no bearing at all on which of us is right. I’m quite sure that Nouriel has more good arguments which favor his position than I do favoring mine. I just think that my arguments are right and that his aren’t. Mostly, our disagreement comes down to theory vs the market. Nouriel bases his arguments on theory, and if there are bearish signals in the market, then he’ll use them to bolster his case; otherwise, the market is wrong. Me, I start from a position of ignorance with respect to much economic theory, and simply look empirically at the fact that when economists say the market is wrong, the vast majority of time it is the economists who are wrong and the market which is right. So I do the opposite to Nouriel: I base my argument on what the market is saying and if there are economic arguments I’ll use them to bolster my case; otherwise, the economists are wrong. I think that I have the edge here, and Nouriel thinks that he has the edge; it probably all comes down to what timeframe you want to look at. If Nouriel’s bearish for long enough, eventually he’ll be right. But only people without any money in the market can afford the luxury of being wrong until they’re right.