So the lunch with Nassim Nicholas Taleb happened, in a rather pretentious little place on 15th Street, which at least was quiet. I arrived brimming with questions, and left with only a few of them answered, but had a great experience all the same.

I think I’m going to do a more formal Q&A with Taleb when both his book and the first reviews are out – probably by email. But here are a few questions I had going in to the lunch, along with any answers that Taleb gave me, if any. They should at least, give an idea of the kind of questions which get raised by his book.

- Are common economic concepts such as cycles or reversion to mean remotely useful or even meaningful? (I asked Taleb this, and got a general reply about all economics being not only useless but also unethical.)

- What does NNT think of Robin Hanson‘s blog, Overcoming Bias? (Taleb says he doesn’t know it. But he should – there’s enormous overlap between the blog and the book. The blogs he likes the most are Arts & Letters Daily and 3 Quarks Daily. He does read newspapers online, but usually through links from these sites. He’s not interested in news, per se.)

- The “Black Swan” of the title comes from the idea that you can’t confirm a statement like “all swans are white” by observing white swans. Similarly, you can’t prove that OJ Simpson is not a murderer by closely observing him all day and seeing him murder nobody. On the other hand, if you give me two paragraphs and tell you they’re anagrams of each other, I’m likely to pick a letter at random, probably something uncommon like W or Q or Z, and count its occurrences in each of the paragraphs. If the occurrences match, I’ll be more likely to believe you. Is there some kind of real confirmation going on here? Or are all such observations largely meaningless unless and until you’ve either falsified the claim or proved it outright? (Taleb: Yes, there is some confirmation going on.)

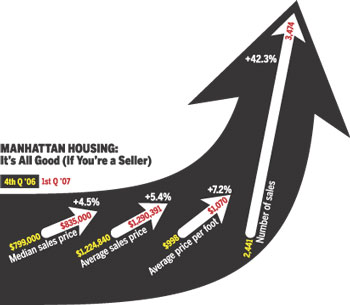

- Housing/property: Would NNT be a buyer or a seller in the current market? (No chance of an answer to that one, despite the fact that Taleb is a good friend of Robert Schiller.)

- NNT’s own investments, which he says are mainly in Treasury bills: Why that, rather than overnight cash? (Unasked.)

- NNT calls himself a “skeptical empiricist”. Does he think that people he meets think themselves to be skeptical empiricists, but aren’t? (Asked. Taleb loves being fooled by randomness, and is not much of a skeptical empiricist in his day-to-day existence. But he certainly is when it comes to investment advice. This led into a broader conversation about skeptics of the past, from Kripke back to Hume and even earlier. Taleb absolutely sees himself in the tradition of the philosopher who destroys epistemic edifices, rather than the philosopher who, after laying out a skeptical position, then tries to overcome it, in the way that Descartes tried to do with his evil demon.)

- NNT draws the distinction between jobs which are scalable – jobs where income can go up a lot without the individual working any harder, such as writing books or trading options – and jobs which are not scalable, such as dentistry or prostitution, where to make more money you basically need to do more work. Taleb has always had scalable jobs, and says that all non-scalable jobs are dull. But what about emergency-room physicians, or homicide detectives, or even magazine journalists? (Taleb conceded this: admitted that, yes, there were non-dull non-scalable jobs. He admires George Soros mainly because Soros is so quick to change his mind or decide that he was wrong about something, and one of the main themes of his book is humility in the face of the fact that we don’t really know anything. So it was easy for him to concede the point: despite the fact that Taleb clearly has a very well-developed ego, he isn’t wedded to being right.)

- NNT says that Syria and Saudi Arabia are more likely to descend into chaos than Italy is, precisely because there has been so little chaos in those countries of late. He contrasts them with Italy, which is built on chaos, and therefore less at risk of it. So does that mean that other stable countries, such as, say, Sweden, are also at risk of chaos? (Unasked.)

- Warren Buffet – skilled, or lucky, or some combination of the two? And isn’t his main business, reinsurance, essentially one big bet against Black Swans? (Taleb said that reinsurers don’t make money, although insurers do: insurers live in what he calls Mediocristan, a world where the law of large numbers applies, and the number of car accidents, say, is predictable and therefore can reasonably be insured against. Reinsurers, on the other hand, live in Extremistan, a world with 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina and outbreaks of war and other unforeseeable events – and that’s a business Taleb would never want to be in. Ironically, however, he is actually in the business of insuring against Black Swans: that’s what the company he’s a part-owner of, Empirica, does. As for Buffett, he’s made his money not through reinsurance so much as by investing the large amounts of cash which come with owning a reinsurer. Is that luck or skill? Unasked.)

- In Extremistan, the world in which we live, power laws apply where the successful become more successful and the unsuccessful become less successful. We can see this in the housing market right now, where New York City prices are stratospheric and rising, while prices in Detroit are at rock-bottom and falling. A Black Swan could hit New York CIty and hurt prices here. But could a positive Black Swan hit Detroit, and send prices there sharply upwards? (Not asked directly. But Taleb did point out that short-term Black Swans are usually negative, such as Hurricane Katrina or Russia’s sudden bond default, while positive Black Swans are usually long term, such as the rise of the internet or even the rise of New York City itself. So if Detroit does become great again, it won’t do so overnight: it takes a lot longer to build a house than to destroy one.)

- Black Swans, by definition, are unexpected. But everybody and their mother these days seems to be forecasting or expecting a housing bust, a credit crunch, a disorderly unwinding of global imbalances, or something along those lines. If that happens, and it’s so widely expected, does that mean it’s not really a Black Swan? Was the equally-forecast popping of the dot-com bubble a Black Swan? (Asked, not really answered.)

- NNT is very rude about the way that finance and economics types measure risk, with things like Value-at-Risk measurements and companies like RiskMetrics. Does that mean that Basel II is actually riskier than Basel I? Does it also mean that the CAPM should be discarded? Is investing money in such a way as to keep up with the S&P 500 with just one-third of its volatility not nearly as impressive an achievement as most financial professionals would have you believe? (Not asked directly, because Taleb was very keen that he hasn’t written a finance book. He wants his book to be found in the Philosophy section, not the Finance section, of bookstores, and will volunteer that its genre is “philosophy of history”.)

- NNT, in his book emphasizes the “narrative fallacy” and the idiocy of believing that we can really or ever know the cause of any events in the real world. Where does that leave, say, monetary policy? If we can’t say that cutting interest rates caused the economy to grow, then what is a central banker to do? (Taleb did inch towards conceding some causality: he said that if a central bank raised interest rates and then there was a recession, you can reasonably claim that the rate hike caused the recession. But he also said that the economic forecasts on which central banks base their actions are worthless, and that even broad economic numbers such as GDP are much less useful than most economists believe.)

- Does NNT buy insurance? (Yes.)

And here’s a few other things I learned over the course of the lunch:

- Taleb was a bit mistrustful of Dan Gilbert’s book Stumbling on Happiness, which I loved, because he felt that Gilbert spent too much time on the jokes and the artful prose, rather than getting straight to the point. This is true, although I’m not sure it’s all that much of a criticism.

- Taleb’s first* book, Fooled by Randomness, is now the biggest-selling book published in 2001. This puts into some perspective his anecdotes about a fictional Russian writer named Yevgenia Krasnova, whose first book, A Story of Recursion, is a surprise and runaway global bestseller. Interestingly, her second book, The Loop, is something of a dud.

- Taleb says that options prices didn’t actually change much if at all in the wake of the invention of the universally-used Black-Scholes method of pricing option. In other words, Black-Scholes was much less useful than you might think.

- Taleb, for all that he refuses to invest in the stock market and writes books full of rhetoric destroying much that we hold dear, is actually not a bear or a pessimist. ” I am convinced that the future of America is rosier than people claim — I’ve been hearing about its imminent decline ever since I started reading,” he writes at edge.org. ” The world is giving us more ‘cheap options’, and options benefit principally from uncertainty. So I am particularly optimistic about medical cures.”

- One thinker who shares Taleb’s love of destroying sacred cows is Paul Feyerabend. But Taleb tries to be a bit more humble than Feyerabend, and less of what he calls a “poseur”.

- Taleb considers economists, as a group, to be unethical. And most journalists, too. Because they “prolong the narrative fallacy”. He was on staff at a university for a while, but quit when he realized that he couldn’t stand being in the same faculty as people whose entire courses were based on the narrative fallacy. Now he’s pursuing a fellowship which will let him explore his ideas on his own, with a handful of colleagues – but even there he’s going to end up with some kind of presence at a high-profile business school. Taleb would love nothing more than to read books and cogitate in his library, maybe travelling the world occasionally. And he hates answering questions about the practical implications of his book: he’d much rather it was treated as pure philosophy. At the same time, he thinks his philosophy has merit precisely because it’s relevant to the way we think and lead our lives. It’s a delicate balancing act, and I’m not sure that Taleb has quite figured out how to perfect it.

So now we wait: the book is published on April 17, and a lot of reviews should be coming out around that time as well. It’ll be fascinating to see what people make of it – and if we’re lucky, we might even be able to get some response from Taleb to the reviews on this blog.

*OK, technically not his first book. His real first book was called Dynamic Hedging: Managing Vanilla and Exotic Options, and it’s available at Amazon for $63. But FBR was his first book for a general audience.

A Dow Jones Factiva search shows that the number of stories mentioning “subprime” and “contained” at the end of last year averaged around 110 or so — but that more than doubled in February, and jumped to a whopping 981 in March. This is hardly a scientific approach, but could be a measure of the urgency with which pundits have been trying to reassure investors the subprime mess won’t spill over.

A Dow Jones Factiva search shows that the number of stories mentioning “subprime” and “contained” at the end of last year averaged around 110 or so — but that more than doubled in February, and jumped to a whopping 981 in March. This is hardly a scientific approach, but could be a measure of the urgency with which pundits have been trying to reassure investors the subprime mess won’t spill over.