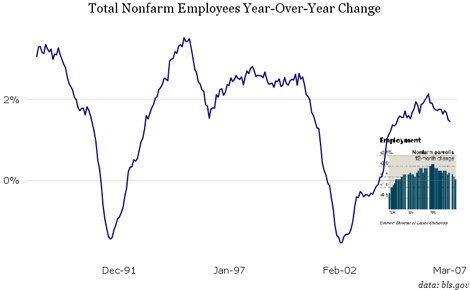

Dan Gross is writing about bank branches in Slate. It seems that in current boom times, the number of branches is expanding even as the number of banks is contracting:

According to the Federal Reserve, even as the number of banking companies falls each year, the number of branches rises steadily.

At the same time, in bust times, the number of branches is likely to contract even as the number of banks… contracts:

When the banking business goes south, or if the economy slips into recession , branches, with their high fixed costs, quickly become a liability. In 1993, for example, the number of bank branches fell by nearly 1,000, according to the Federal Reserve. In 2000, a net 1,859 branches were closed. (The number of branches didn’t regain the 1999 peak until 2002.) Indeed, the ability to save money by shuttering overlapping branch networks is one of the factors that helps drive bank mergers during periods of sluggish economic growth.

The main conclusion to draw from all this is that the number of banks in the US is going to continue to fall, no matter what happens to the economy. That is actually a good thing: the US has too many small banks, which consume vast amounts of regulatory time and energy to no particularly useful end. Indeed, the various regulators (FDIC, OCC, Treasury, Federal Reserve, etc) are likely, at the margin, to constrain the actions of the big banks because they’re worried about giving similar freedoms to small banks, and want to keep a flat competitive playing field.

In other words, let’s have more bank consolidation. Quite clearly, reducing the number of banks has no adverse impact on the number of bank branches.

The NYT has an interesting chart accompanying its

The NYT has an interesting chart accompanying its