Bob Litan, formerly of the Kauffman Foundation and the Brookings Institution, has recently taken up a new job as director of research for Bloomberg Government, where he’s going to have to be transparent and impartial. But one of his last gigs before moving to Bloomberg — a paper on the subject of people borrowing money from their 401(k) accounts — was neither of those things.

To understand what’s going on here, first check out Jessica Toonkel’s article from Friday about Tod Ruble and his company, Custodia.

Tod Ruble is trying to sell retirement plan insurance that employers say they do not want and their employees may not need.

But the Dallas-based veteran commercial real estate investor is not letting that stop him. Since late 2010, he has started up a company, Custodia Financial, and spent more than $1 million pushing for legislation that would allow companies to automatically enroll employees who borrow from their 401(k) plans in insurance that could cost hundreds of dollars a year.

Once you’ve read that, go back and check out a spate of stories that hit a series of major news outlets in July. Alan Farnham of ABC News, for instance, ran a story under the headline “401(k) Loan Defaults Skyrocket”:

A new study estimates that such defaults might total $37 billion a year, a sharp increase from 2007, when defaults totaled only $665 million.

Similarly, check out Walter Hamilton, in the Chicago Tribune (and LA Times): the headline there is “Defaults on 401(k) loans reach $37 billion a year”. At Time, Dan Kadlec also ran with the $37 billion number, saying that “the default rate on these loans has skyrocketed since the recession”. Similar stories came from Blake Ellis at CNN Money (“Loan defaults drain $37 billion from 401(k)s each year”), Mitch Tuchman at MarketRiders (“401k Loan Default Time Bomb Is Ticking”), and many others.

The only hint of skepticism came from Barbara Whelehan at BankRate. She noted that the study cited Kevin Smart, CFO of Custodia Financial, as a source — and she also noted that “it would be a boon for the insurance industry to get the rules changed, and it is working behind the scenes to do just that. In April, Custodia Financial submitted a statement to the House & Ways Committee arguing for automatic enrollment into insurance coverage for 401(k) loans.”

Whelehan also smelled something fishy in the way the paper was paid for:

This paper by Navigant Economics, which made a big splash in the press, was financially supported by Americans for Retirement Protection. That organization has a website, ProtectMyRetirementBenefits.com, but no “about us” link. It does give you the opportunity to sign a petition demanding protection of retirement funds through insurance. Take a look at it, and see if you think the website was created by average Americans or by the insurance industry.

Whelehan was actually breaking news here: there’s no public linkage between Americans for Retirement Protection, the organization which paid for the paper, and the astroturf website. In fact, Americans for Retirement Protection seems to have no public existence at all, beyond a footnote in the paper, which was co-authored by Bob Litan and Hal Singer.

Enter Toonkel, writing her story about Custodia. In the course of her reporting, she discovered — and Custodia confirmed — that Americans for Retirement Protection, and ProtectMyRetirementBenefits.com, are basically alter egos of Custodia itself. Custodia would welcome other organizations joining in, but that’s unlikely to happen, because Custodia owns the patents on the big idea that the paper and the website are pushing — the idea that 401(k) loans should come bundled with opt-out insurance policies.

Once you’re armed with this information, it’s impossible not to look at the Litan-Singer paper in a very different way. Its abstract concludes: “We demonstrate that the social benefits of steering (but not compelling) plan participants towards insurance when they borrow are likely positive and economically significant.” And yet nowhere in the paper is there any indication that it was bought and paid for by the very company which has a patent on doing exactly that.

And what about that $37 billion number? Are defaults on 401(k) loans really as big a problem as the paper says that they are? After all, the smaller the problem, the less important it is to introduce an expensive fix for it.

The simple answer is no: 401(k) loan defaults are not $37 billion per year. But the fact is that nobody knows for sure exactly where they are, which makes it much easier to come up with exaggerated estimates. As the paper itself admits, “the sum total of 401(k) defaults ought to be an easily accessible statistic, but it is not”. And the $37 billion, far from being a good-faith estimate, in fact looks very much like an attempt to get the largest and scariest number possible.

So how did Litan and Singer arrive at their $37 billion figure? Let’s start with the only concrete numbers we have — the ones from the Department of Labor, whose most recent Private Pension Plan Bulletin gives a wealth of information about all private pension plans in the country. Every pension plan has to file something called a Form 5500, and the bulletin aggregates all the numbers from all the 5500s which are filed; the most recent bulletin gives data from 2009.

This bulletin has two datapoints which are germane to this discussion. First of all, there’s Table A3, on page 7 of the bulletin (page 11 of the PDF). That shows that loans from defined-contribution pension plans to their own participants totaled $51.7 billion in 2009. Secondly, there’s Table C9, the aggregated income statement for the year. If you look at page 32 of the bulletin (page 35 of the PDF), you’ll see a line item called “deemed distribution of participant loans”, which came to $670 million for the year. If you borrow money from your 401(k) and you don’t pay it back, then that money is deemed to have been distributed to you, and counts as a default. So we know that the official size of 401(k) defaults in 2009 was $670 million — a far cry from Litan and Singer’s $37 billion.

Now the $670 million figure does not account for all 401(k) defaults. Most importantly, in some situations, if you default on a 401(k) loan after having been fired from your job, then the money is counted as an “actual distribution” rather than as a “deemed distribution”.

The Litan-Singer paper goes into some detail about this. “According to a recent study by Smart (2012),” they write, “although Form 5500 reflects actual distributions, there is no way to determine the amount of actual defaults.” They then look in detail at Smart’s figures, footnoting him five consecutive times, and treating him as an undisputed authority on such matters. Their citation is merely “Kevin Smart, The Hidden Problem of Defined Contribution Loan Defaults, May 2012.”

Where might someone find this paper? Here, since you ask: it’s helpfully hosted at CustodiaFinancial.com. And on the front page of the paper, Kevin Smart is identified as the “Chief Financial Officer, Custodia Financial”.

There’s no indication whatsoever in the Litan-Singer paper that the “Smart” they cite so often is the CFO of Custodia Financial, the company which has the most to gain should their recommendation be accepted. And there’s certainly no indication that he’s essentially their employer: that Custodia paid them to write this paper. In fact, the name Custodia appears nowhere in the Litan-Singer paper at all.

It’s instructive to look at the Smart paper’s attempt to estimate the magnitude of the 401(k) default problem. I’ll simplify a little here, but to a first approximation, Smart assumes that 12% of people with 401(k) loans lose their jobs. He also assumes that if you lose your job when you have a 401(k) loan, there’s an 80% chance you’ll default on that loan. As a result, he comes up with a 9.6% default rate on 401(k) loans. He then multiplies that 9.6% default rate by total 401(k) loans of $51.7 billion, adds in some extra defaults due to death and disability, and comes up with a grand total of $6.2 billion in loan defaults per year, excluding the “deemed distributions” of $670 million. Call it $7 billion in total, of which $6 billion could be protected by insuring loans against unemployment, death, and disability.

Now remember that this is a paper written by the CFO of Custodia Financial — someone who clearly has a dog in this race. It’s in Smart’s interest to make the loan-default total look as big as possible, since the bigger the problem, the more likely it is that Congress will agree to implement Custodia’s preferred solution.

But when Litan and Singer looked at Smart’s paper, they weren’t happy going with his $6 billion figure. Indeed, as we’ve seen, their paper comes up with a number six times larger. So if even the CFO of Custodia only managed to estimate defaults at $6 billion, how on earth do Litan and Singer get to $37 billion?

It’s not easy. First, they double the total amount of 401(k) loans outstanding, from $52 billion to $104 billion. Then, they massively hike the default rate on those loans, from 9.6% to 17.9%. And finally, they add in another $12 billion or so to account for the taxes and penalties that borrowers have to pay when they default on their loans.

It’s possible to quibble with each of those changes — and I’ll do just that, in a minute. But it’s impossible to see Litan and Singer compounding all of them, in this manner, without coming to the conclusion that they were systematically trying to come up with the biggest and scariest number they could possibly find. It’s true that whenever they mention their $37 billion figure, it’s generally qualified with a “could be as high as” or similar. But they knew what they were doing, and they did it very well.

When the Chicago Tribune and the LA Times say in their headlines that 401(k) loan defaults have reached $37 billion a year, they’re printing exactly what Custodia and Litan and Singer wanted them to print. The Litan-Singer paper doesn’t exactly say that defaults have reached that figure. But if you put out a press release saying that “the leakage of funds in 401(k) plans due to involuntary loan defaults may be as high as $37 billion per year”, and you don’t explain anywhere in the press release that “leakage of funds” means something significantly different to — and significantly higher than — the total amount defaulted on, then it’s entirely predictable that journalists will misunderstand what you’re saying and apply the $37 billion number to total defaults, even though they shouldn’t.

But let’s backtrack a bit here. First of all, how on earth did Litan and Singer decide that the total amount of 401(k) loans outstanding was $104 billion, when the Department of Labor’s own statistics show the total to be just half that figure? Here’s how.

First, they decide that they need the total number of active participants in defined-contribution pension plans. They could get that number — 72 million — from the Labor Department bulletin: it’s right there in the very first table, A1. But the bulletin isn’t helpful to them, as we’ve seen, so instead they find the same number in a different document from the same source.

That’s as much Labor Department data as Litan and Singer want to use. Next, they go to the Investment Company Institute, which has its own survey, covering some 23 million of those 72 million 401(k) participants. According to that survey, in 2011, 18.5% of active participants had taken out a loan; Litan and Singer extrapolate that figure across the 401(k) universe as a whole.

Finally, Litan and Singer move on to Leakage of Participants’ DC Assets: How Loans, Withdrawals, and Cashouts Are Eroding Retirement Income, a 2011 report from Aon Hewitt which is based on less than 2 million accounts, of the 72 million total. According to the Aon Hewitt report, which doesn’t go into any detail about methodology, when participants took out loans, “the average balance of the outstanding amount was $7,860”. Needless to say, that number was never designed to be multiplied by 72 million, as Litan and Singer do, to generate an estimate for the total number of loans outstanding.

If you want an indication of just how unreliable and unrepresentative the $7,860 number is, you just need to stay on the very same page of the Aon Hewitt report, which says that 27.6% of participants have a loan. If Litan and Singer think that the $7,860 figure is reliable, why not use the 27.6% number as well? If they did that, then the total number of 401(k) loans outstanding would be $7,860 per loan, times 72 million participants, times 27.6% of participants with a loan. Which comes to $156 billion.

But of course we know that there were just $51.7 billion of loans outstanding in 2009; evidently Litan and Singer reckoned that it just wouldn’t pass the smell test if they tried to get away with saying that number might have trebled in a single year. So they confined themselves to merely doubling the number, instead.

Litan and Singer give no reason to mistrust the official $51.7 billion number, except to say that it’s “outdated”. But if it’s outdated, it’s only outdated by one year: it’s based on 2009 data, while the much narrower surveys that Litan and Singer cite are generally based on 2010 data. At one point, they cite the ICI survey to declare that there is “an estimated $4.5 trillion in defined contribution plans”, despite the fact that the much more reliable Labor Department report shows that there was just $3.3 trillion in those plans as of 2009. This, I think, quite neatly puts the lie to the Litan-Singer implication that the problem with the Labor Department numbers is merely that they are out of date, and that when we get numbers for 2010 or 2011, they might well turn out to be in line with the Litan-Singer estimates. There’s simply no way that total DC assets rose from $3.3 trillion to $4.5 trillion in the space of a year or two.

In other words, whatever advantage the ICI and Aon Hewitt surveys have in terms of timeliness, they more than lose in terms of simply being based on a vastly smaller sample base. Litan and Singer adduce no reason whatsoever to believe that the ICI and Aon-Hewitt surveys are in any way representative or particularly accurate, despite the fact that the discrepancies between their figures and the Labor Department figures are prima facie evidence that they’re not representative or particularly accurate. If the ICI and Aon Hewitt surveys were all we had to go on, then I could understand Litan-Singer’s decision to use them. But given that the Labor Department already has the number they’re looking for, it just doesn’t make any sense that they would laboriously try to recreate it using less-reliable figures.

It’s true that the Labor Department’s figures do undercount in one respect: they cover only plans with 100 or more participants — and therefore cover “only” 61 million of the 72 million active participants in DC plans. If Litan and Singer had taken the Labor Department’s numbers and multiplied them by 72/61, or 1.18, that I could understand. But disappearing into a rabbit-warren of private-sector surveys of dubious accuracy, and emerging up with a number which is double the size of the official one? That’s hard to justify. So hard to justify, indeed, that Litan and Singer don’t even attempt to do so.

That, indeed, is the strongest indication that the Litan-Singer paper can’t really be taken seriously. For all their concave borrower utility functions and other such economic legerdemain, they simply assert, rather than argue, that they “believe” it is “more appropriate” to use private-sector surveys rather than hard public-sector data. Such decisions cannot be based on blind faith: there have to be reasons for them. And Litan-Singer never explain what those reasons might be.

Now the move from public-sector to private-sector data merely doubles the total size of the purported problem, while Litan-Singer are much more ambitious than that. So their next move is to bump up the default rate on loans substantially.

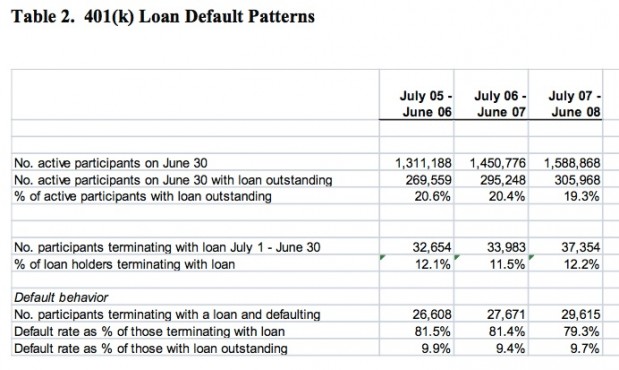

There’s no official data on default rates at all, so Litan and Singer, following Smart’s lead, decide to base their sums on a Wharton paper from 2010. Once again, they have to extrapolate from a very small sample: the Wharton researchers had at their disposal a dataset covering 1.5 million plan participants (just 2% of the total). Looking at what happened over a period of three years, from July 2005 to June 2008, the researchers found that the number of terminations, and the number of defaults, remained pretty steady:

These are the numbers that Smart used in his paper: roughly 12% of loan holders being terminated each year, and roughly 80% of those defaulting on their loans.

But these are not the numbers that Litan-Singer use. Instead, they notice that the overall default rate, as a percentage of overall loans outstanding, was roughly double the national unemployment rate at the time. And so since the unemployment rate doubled after June 2008, they conclude that the default rate on outstanding 401(k) loans probably doubled as well.

Do they have any evidence that the default rate on 401(k) loans might have doubled after 2008? No. Well, they have a tiny bit of evidence: they look at the small variations in default rates in each of the three years covered in the Wharton study, and see that those variations move roughly in line with the national unemployment rate. Never mind that the default rate fell, from 9.9% to 9.7%, between 2006 and 2008, even as the unemployment rate rose, from 4.8% to 5.0%. They’ve still somehow managed to convince themselves that it’s reasonable to assume that the default rate today is nowhere near the 9.6% seen in the Wharton survey, and in fact is probably closer to — get this — 17.9%.

This doesn’t pass the smell test. The primary determinant of the default rate, in the Wharton study, was the percentage of loan holders who wound up having their employment terminated, for whatever reason. And so what Litan-Singer should be looking at is the increase in the probability that any given employee will end up being terminated in any given year.

Remember that in any given month, or year, the number of people fired is roughly equally to the number of people hired. When the former is a bit larger than the latter for an extended period, then the unemployment rate tends to go up; when it’s smaller, the rate goes down. But the churning in the employment economy is a constant, even when the unemployment rate is very low.

When the unemployment rate rose after 2008, that was a function of the fact that the number of people being fired was a bit higher than normal, while the number of people being hired was a bit lower than normal. But looked at from a distance, neither of them changed that much. In terms of the Wharton study, what we saw happening to the unemployment rate is entirely consistent with the percentage of loan-holders being terminated, per year, staying pretty close to 12%. Of course it’s possible that number rose sharply, but it’s really not possible that number rose as sharply as the unemployment rate did. And so I find it literally incredible that Litan and Singer should decide to use the national unemployment rate as a proxy for the number of people whose employment is terminated each year.

Well, maybe not literally incredible — the fact is there’s one very good reason why they might do that. Which is that they were being paid by Custodia to use any means possible to exaggerate the number of annual 401(k) loan defaults.

Litan and Singer do actually provide a mini smell test of their own: they say that their hypothesized rise in 401(k) loan defaults is more or less in line with the rise in, say, student-loan defaults or in mortgage defaults over the same period. But those statistics aren’t comparable at all, because Litan and Singer are already assuming that the default rate on 401(k) loans, among people who lose their job, was a whopping 80% before the financial crisis. There’s a 100% upper bound here: you can’t have a default rate of more than 100%. Remember that the whole point of this paper is to provide the case that people taking out 401(k) loans should insure themselves against unemployment: any rise in the default rate from people who don’t lose their job (or die, or become disabled) is more or less irrelevant here. And when your starting point is a default rate of 80%, there really is a limit to how much that default rate can rise; it’s certainly going to be difficult to see it rise by more than 85%, even if you allow a simultaneous increase in the number of people being terminated.

All of this massive exaggeration has an impressive effect: if you take $104 billion in loans, and apply a 17.9% default rate, then that comes to a whopping $18.6 billion in 401(k) loan defaults every year. A big number — but still, evidently, not big enough for Litan and Singer. After all, their number is $37 billion: double what we’ve managed to come up with so far. We’ve already doubled the size of the loan base, and almost-doubled the size of the default rate, so how on earth are we going to manage to double the total again?

The answer is that LItan and Singer, at this point, stop measuring defaults altogether, and turn their attention to a much more vaguely-defined term called “leakage”. Once again, they decide to outsource all their methodology to Custodia’s CFO, Kevin Smart. The upshot is that if you borrowed $1,000 from your 401(k) and then defaulted on that loan, the amount of “leakage” from your 401(k) is deemed to be much greater than $1,000. Litan and Singer first add on the 10% early-withdrawal penalty that you get charged for taking money out of your plan before you retire. They also add on the income tax you have to pay on that $1,000, at a total rate of 30%. (They reckon you’ll pay 25% in federal taxes, and another 5% in state taxes.) So now your $1,000 default has become a $1,400 default.

How does that extra $400 count as leakage from the 401(k), rather than just something that gets added to your annual tax bill? Smart explains:

Most participants borrow from their retirement savings because they are illiquid and do not have access to other sources of credit. This clearly demonstrates that participants who default on a participant loan do not have the financial means to pay the taxes and penalty. Unfortunately, their only source of capital is their retirement savings plan so many take the remaining account balance as an additional early distribution to pay the taxes and penalty, further increasing the amount of taxes and penalties due. These taxes and penalties become an additional source of leakage from retirement assets.

Smart’s 16-page paper has no fewer than 24 footnotes, but he fails to provide any source at all for his assertion that “many” people raid their 401(k) plans in order to pay the taxes on the money they’ve already borrowed. In any event, Smart (as well as Litan and Singer, following his lead) makes the utterly unjustifiable assumption that not only many but all 401(k) defaulters end up withdrawing the totality of their penalties and extra taxes from their retirement plan. And then, just for good measure, because that withdrawal also comes with a penalty and taxes, they apply a “gross-up” to that.

By the time all’s said and done, the $1,000 that you lent yourself from your 401(k) plan, and failed to pay back in a timely manner, has become $1,520 in “leakage”. Add in some extra “leakage” for people who default due to death or disability (apparently even dead people raid their 401(k) plans to pay income tax on the money they withdrew), and somehow Litan and Singer contrive to come up with a total of $37 billion.

It’s an unjustifiable piling of the impossible onto the improbable, and the press just lapped it up — not least because it came with the imprimatur of Litan, a genuinely respected economist and researcher. Custodia hired him for precisely that reason: they knew that if his name was on the front page of a report, that would give it automatic credibility. But for exactly the same reason, Litan had a responsibility to be intellectually honest when writing this thing.

Instead, he never even questioned any of the assumptions made by Custodia’s CFO. For instance: if you’re terminated, and you default on your 401(k) loan, what are the chances that the money you received will end up being counted as an “actual distribution” rather than as a “deemed distribution”? Smart and Litan and Singer all implicitly assume that the answer is 100%, but they never spell out their reasoning; my gut feeling is that it’s not nearly as clear-cut as that, and that it all depends on things like when you lost your job, when you defaulted, and who your pension-plan administrator is.

Custodia’s business, and the Litan-Singer paper, are based on the idea that if people who borrowed money from their 401(k) plans had insurance against being terminated from their jobs, then that would have significant societal benefit. In order for the societal benefit to be large, the quantity of annual 401(k) loan defaults due to termination also has to be large. But right now, there’s not a huge amount of evidence that it actually is: in fact, we really have no idea how big it is.

I can say, however, that Custodia has already won this battle where it matters — in the press. “Protecting 401(k) savings from job loss makes a lot of sense,” said Time’s Kadlec in his post — and so long as Custodia can present lawmakers with lots of headlines touting the $37 billion number and supporting their plan, Litan and Singer will have done their job. The truth doesn’t matter: all that matters is the headlines, and the public perception of what the truth is.

Come to think, maybe this makes Litan the absolutely perfect person to run the research department at Bloomberg Government. On the theory that it takes a thief to catch a thief, Bloomberg has hired someone who clearly knows all the tricks when it comes to writing papers which come to a predetermined conclusion. And he also has a deep understanding of the real purpose of most of the white papers floating around DC: it’s not to get closer to the truth, but rather to stamp a superficially plausible institutional imprimatur onto a policy that some lobbyist or pressure group desperately wants enacted. I can only hope that in the wake of using his talents in order to serve Custodia Financial, Litan will now turn around and use them in order to serve rather greater masters. Like, for instance, truth, and transparency, and intellectual honesty.

LOL @ your LSD banner.

Good article Felix. Thank goodness there are still bright people like Whelehan and Toonke who can look deeper than the charts and supposed “facts and figures.”

But, is anyone really surprised that dubious information becomes the “truth” when Wikipedia has the “answer” for research, reference and cross checking? This is the new normal…for a dumbed-down, fake society of twits who can’t spell, communicate or go outside to meet real people and a journalist’s dream…with a wealth of streaming, and sometimes steaming, information at their fingertips. *click*

At first glance, it seemed websites were geared towards a consumer’s convenience and savings, but in fact the internet is one very large ad space with lots of fake websites to lure us in, mark us with cookies and take our information to use against us. Caveat Emptor

Nice article Felix, good thing they are able to expose facts but your LSD banner is hillarous.